With temperatures hitting record lows in Scandinavia at the start of winter and parts of Swedish Lapland shivering at -44C, flocks of keen birdwatchers across the UK are rejoicing in a "waxy winter".

Thousands more waxwings than usual have been reported in the UK this season, with several hundred strong flocks recently reported as far south as the Peak District and London. Waxwings do not usually go further south than East Anglia.

Can the extreme Nordic cold and the so-called waxwing winter be directly linked?

Well, it's a bit more complicated than that, as Dr Viola Ross-Smith of the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) explains. "Waxwings have a so-called catastrophic migration which means their autumn and winter movements are mainly driven by the need to find enough food.

"They came to the UK when the berry harvest was poor in Scandinavia but most of the thousands of birds that are here now have returned in late autumn."

So while January's frozen berries at home may have driven some hungry waxwings further south and west to our shores, it seems most birds arrived earlier rather than when temperatures so dramatically dropped in northern Europe.

An explanation for this can be found in autumn temperatures.

Although much of Scandinavia saw a particularly warm September, in October and November 2023, temperatures fell well below seasonal averages. It was the coldest October since 2009 for Norway and the coldest November for 14 years in most of Sweden.

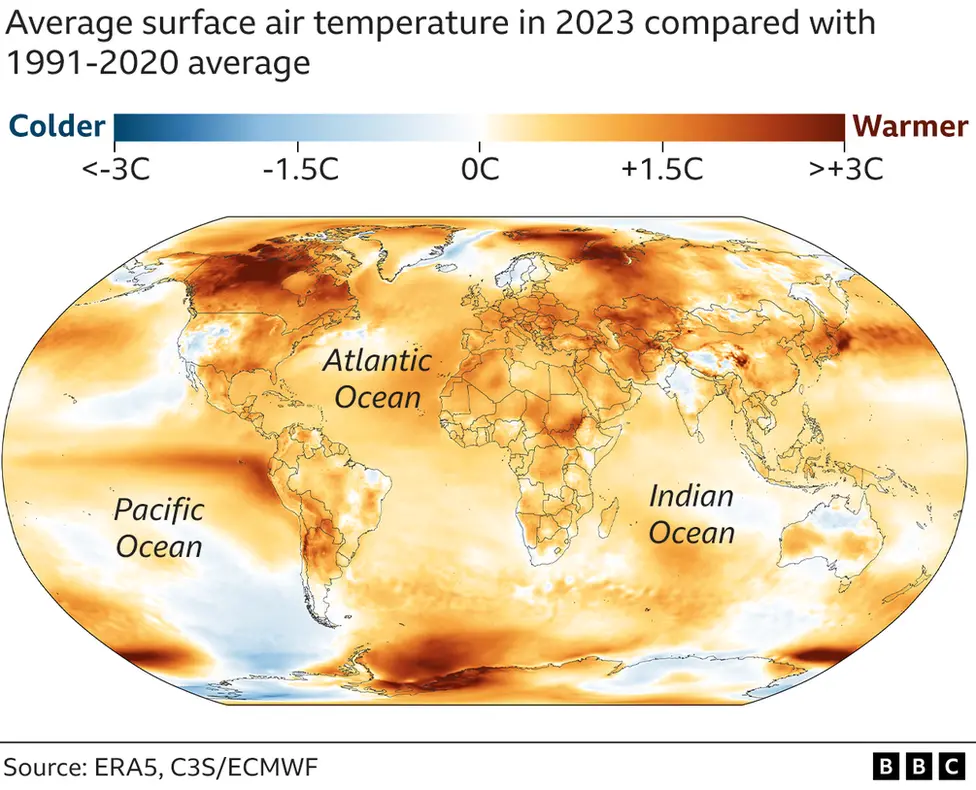

And interestingly, even though 2023 was the warmest year on record globally, the excess heat was not spread evenly across the planet. As the global temperature anomaly map above shows, much of the Scandinavian peninsula is one of the few places on Earth where temperatures were below average.

Could this contribute to the current flow of wax wings? And does this mean we could be in for a repeat performance in the UK this coming autumn with even more flocks of this brilliant audience?

American audience

Changes in weather and climate in general certainly affect our bird populations. Last September saw the largest influx of American landbirds into the UK in recorded history.

How did this rather lost bird get to the UK? During their annual migration south across the North American continent to the Gulf of Mexico, they were likely caught in Hurricane Lee, which itself was moving up the eastern seaboard and pushed back north.

The remnants of the hurricane were then caught up in the jet stream and crossed the Atlantic, dumping bewildered migrants on the west coast of Great Britain. Unfortunately, due to the wind direction they are not able to breed or return home.

And they were lucky birds. Many others would have drowned in the Atlantic and met a tragic fate.

It is likely that as the world warms and hurricanes become stronger and more frequent, these events will become more frequent.

The long-term effects of climate change on bird populations are also significant due to increased air and sea surface temperatures. Seabirds such as arctic terns and Atlantic puffins are particularly vulnerable. The BTO predicts a catastrophic decline of up to 90% in puffin numbers by 2050.

Birds catch insects in the morning

Similarly the cuckoo is also a falling bird.

It has struggled to match the timing of its arrival in the UK from central Africa with the current spring warmth and as a result succulent food sources such as newly hatched caterpillars are being lost.

Good news?

A warming climate has, however, allowed some species to colonize the UK and they are now thriving. As Dr Ross-Smith points out, the little egret did not breed at all in the British Isles before 1996, but is now fairly common. Its southern European cousins the Great White Egret and the Cattle Egret are beginning to follow its lead.

Similarly, colorful bee-eaters, Mediterranean gulls and black-winged stilts are becoming more familiar sights.

As, potentially, are waxwings.